Haunted by Past Jobs, New Hires Are Quietly Burning Out

Work-induced trauma leaves many new hires on eggshells, afraid to ask for support.

You’re reading the newsletter of Hear Me Out. We talk to employees off the record, then help their leaders make work more rewarding. Learn about our service.

“I think I’ve got workplace trauma,” an employee once told me, reflecting on their onboarding. They knew, rationally speaking, that their new employer cared about work-life balance. But their last job, where long hours and short lunches were the norm, continued to haunt them. While the company assured them it was ok to log off, they told me, they still worried their hours were being monitored.

In the context of a business relationship, the word trauma might feel like overkill. But the workplace is an intimate space. We spend most of our time with our coworkers, whether in person or virtually. With so much of our lives tied to work, from healthcare to retirement to our very identities, managers and colleagues hold the keys to our financial and emotional wellbeing. And like a promising first date that turns into a nightmare relationship, a deeply negative work experience—one so bad, it affects how you approach other relationships later—can rightly be called traumatic.

Experience has taught many new hires to tough it out in silence, even to the point of burning out.

In this context, employees have good reason to be wary of professional love-bombing. And lately, employers are spreading the love on thick. In a competitive hiring market, candidates see a lot of vague, unenforceable platitudes about putting people first and valuing work-life balance. Companies see this kind of language as savvy employer branding, but to traumatized employees, it just reads as empty promises.

When new hires inevitably get stuck, experience has taught many to tough it out in silence, even to the point of burning out. No one wants their new boss to think they need too much hand-holding. Other than slowly and steadily building trust, there’s no way to reverse the trauma of an always-on culture or a job where—as the saying goes—when you bring a problem, you become the problem.

Comfort with direct communication is a privilege

This is where a skeptical executive might jump in with an appeal to personal responsibility. Shouldn’t employees take ownership over their own growth? And if some of them can’t, why not just hire people who are more direct? That’s a nice idea, in theory. But in reality, comfort with direct communication is a privilege.

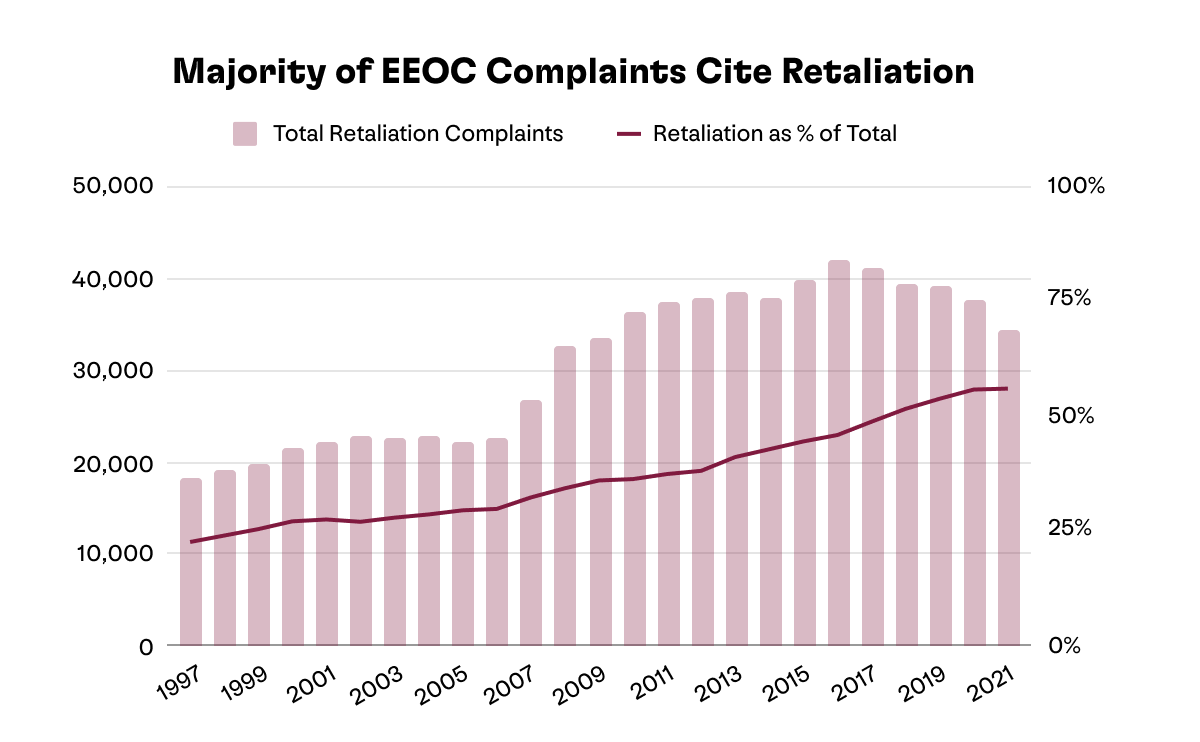

Speaking up at work has not, historically speaking, gone very well for the oppressed. Retaliation for reporting discrimination is the top complaint to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. It’s also increasingly common, showing up in 56% of reports in 2021, up from 27% in 2000. And data from Textio suggests women are 11 times more likely than men to be labeled as “abrasive” in performance feedback. In the same survey, Black and Latinx people reported being called “passionate” (code for “can’t get along with others”) twice as often as their white and Asian colleagues.

For immigrants, the stakes can be even higher. When your job is your visa, losing it can derail a lot more than your career. It can derail your life, your spouse’s life, and your kids’ education. Talking to your boss about why you’re struggling and close to burnout (in a second or third language, no less!) isn’t exactly a casual affair.

The effects of work trauma can show up long after bad memories have faded. Amid a public reckoning at Gimlet Media last year, a former employee wrote, “Even though I’m at a new company, I’ve noticed how much I’ve internalized the gaslighting.” They described a “Gimlet PTSD” that manifested as “unconscious curtailing to white colleagues, and silently holding your tongue in fear of retribution.” To the uninformed, this can easily look like a satisfied employee, chugging along.

The business case for trauma-informed management

The residual effects of workplace trauma don’t just harm employees. They take a serious toll on employers, too. Until they ramp up, every new hire is a sunk cost. Their coworkers spend time training them, picking up the slack, and fixing their mistakes.

The cost of new hires goes beyond lost productivity. A surprising number give up, increasing the cost of hiring. In an April 2022 survey, Lattice found 52% were ready to quit within 90 days. Early leavers often blame a lack of support: A 2014 survey from BambooHR found a full third had little to no onboarding, with 15% saying this helped lead them to quit. Allowing managers to stand by while new hires suffer in silence is a terrible business decision.

That doesn’t mean workplaces are stuck. Traumatized employees call for trauma-informed management. That starts by recognizing that most employees are likely to have some kind of trauma that gets in the way of speaking up.

When a new hire says things are going fine, their manager should never assume it’s all sunshine and rainbows. This is true even for outspoken employees: As one large meta-study in the Academy of Management Journal concluded, “People quite often volunteered ideas in order to help their teams even as they silenced their fears.”

Trauma-informed management views the workforce with clear eyes. It shifts the focus from “What’s wrong with this person?” to “What happened to them?”

New hires need to hear over and over that it’s not just ok to ask for help, but strongly encouraged. Vague assurances to “let us know if you need support” strike the same tone as the classic anti-vacation trope, “feel free to take some time if you need it.” By placing the burden on employees to decide if they need support, this approach all but guarantees most won’t ask for help. And managers should ask new hires to reflect on the culture in their last job and how it shapes their expectations for this one.

Coworkers play a role, too. Since new hires confide in peers, they need to know how to respond when a coworker is stuck. Ideally, that means being supportive while gently reminding them it’s the manager’s job to set them up for success.

No one starts a new job with a blank slate. Trauma-informed management views the workforce with clear eyes. It shifts the focus from “What’s wrong with this person?” to “What happened to them?” It accepts that many employees’ past work experiences have left them profoundly cynical. And it resists the urge to blame the vulnerable for their own fears. Because until an employee feels safe in their relationship with work, they’ll never open up—and they’ll always have an eye on the exit.